At a height of 29,029 feet, Mount Everest is the world’s tallest mountain. Located on the Tibetan Plateau, Everest is situated between Nepal and the Tibet autonomous region of China. This area of the Himalayas is often referred to as the “Roof of the World”. Each year hundreds of foreign climbers flock to Everest to try their luck at summiting the once insurmountable mountain. While climbing Everest is seen as a bucket list item by the West, it is a perilous profession for hundreds of Sherpa men. Sherpas are employed as porters on Everest. These men are the unsung heroes of Everest by making the summit dream a reality for many, but at what cost?

Many Sherpas die on Everest every year due to causes that could be prevented by adequate regulations by the Nepali government around foreign climbing companies. The Nepali government has limited the number of novice climbers, changed the routes up Everest, and has even increased life insurance payouts, but many Sherpas argue this is not enough. Failing to protect their own citizen’s working conditions, which results from the constant pressure from the foreign climbing companies, the government has turned its back on the Sherpa community.

Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and New Zealander, Sir Edmund Hillary, became the first people to successfully summit Mount Everest in 1953. Hillary attributes the team’s success to the indispensable aid of the Sherpas. These indigenous people believe that Everest is sacred and is the spirit of the Mother Goddess of the World manifests in the mountain. Before even setting foot on Everest, the Sherpas conduct a Puja ceremony where they ask for a safe journey to the summit.

The Sherpa culture adheres to the religious traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. They are an ethnic group in regions of Nepal, India, and Tibet known for their extreme athleticism in high altitudes. Foreign climbing companies have hired Sherpas to be porters on their Everest expeditions. They are essential to any expedition as they carry the heavy gear, install ropes and ladders along the route, and serve as a high altitude guide. They carry the heavy loads of equipment up and down Everest multiple times making them more susceptible to the risk of avalanches, frostbite, and death. According to CNN, a Sherpa can expect to earn up to $5,000 a climbing season. This amount is roughly five times the average Nepali salary. However, this salary is not seen as a fair price to pay considering the risks of a high altitude job.

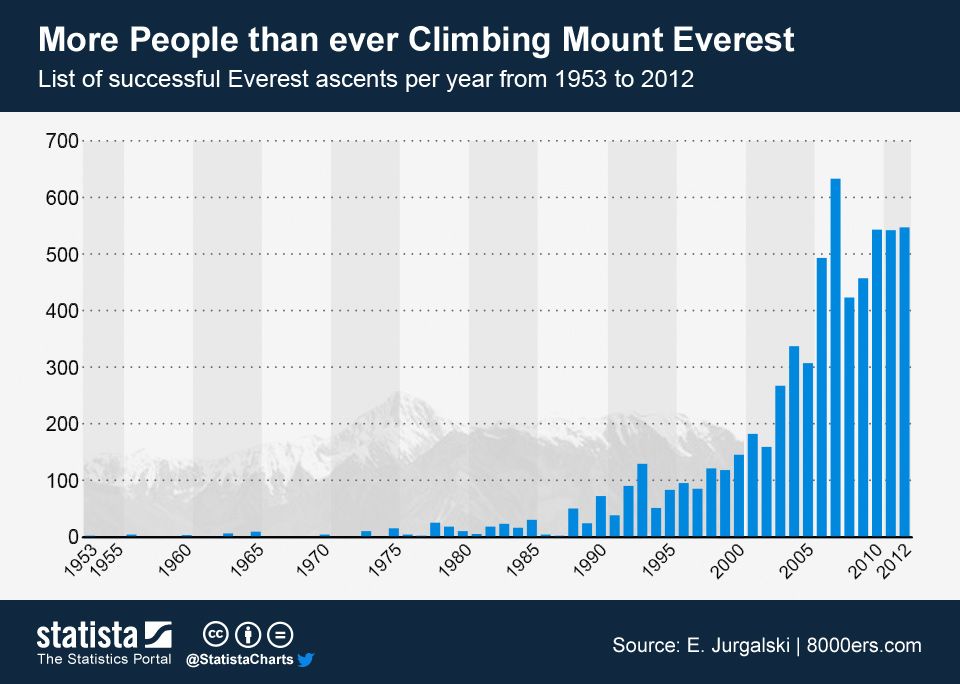

In the 1990’s, the improvements to mountaineering equipment became the catalyst for an increase of commercial Everest expeditions.

This study shows the growing number of successful summits on Everest per year. The years where the number spikes tend to represent a climbing season with ideal weather. The month of May is typically the only month where the conditions are good enough to reach the summit. This can cause teams to scramble to the top when they see a window of a few days. The weather on Everest is highly volatile offering little to no margin for error on a miscalculation.

This picture taken on Everest looks like a line at Disney World and not a scene that should occur at 26,000 ft above sea-level. People are having to wait for hours in subzero conditions to reach the summit of Everest. Everest blogger, Alan Arnette, calculated that five out of the eleven deaths during the 2019 climbing season could have been caused by the crowds. Alpine Ascents guide, Eric Murphy stated in a National Geographic interview that “If you keep going to the summit when you don’t have enough oxygen to get back down, that’s poor decision making. The slow-moving lines are a leadership problem with the expedition leaders more than anything else.” These leaders face intense pressure from their clients to summit Everest. This pressure to get as many clients as possible to the summit has also resulted in waves of novice climbers wanting to conquer Everest without adequate experience or training. These climbers are not only endangering themselves, but also the Sherpas that are there to guide them. Often feeling entitled to the summit, these climbers will ignore the warnings of their Sherpas in order to have their moment of glory on the worlds’ tallest mountain.

A young Sherpa, Sange, recalls his near death experience in a HBO interview. He states how he tried to warn his client that the climb “was doomed and they must turn back”. Pursuing the summit would not just threaten his client’s life, but it would also put him in extreme danger. His client responded that he “paid a lot of money to the Nepali government and to Sange’s company”. This put Sange in a situation where he would have to decide between saying himself or tarnishing the “Sherpa name” by abandoning his client. Sange and his client pushed on to successfully summit the mountain, but did not possess enough energy to safely return to base camp. They were rescued by a team of Sherpas. Sange was on the verge of death, but miraculously survived. However it cost Sange his hands as he lost them due to frostbite. He had to stop being a porter on Everest as a result.

The climbing companies and the Nepali government have directly profited from the growing number of climbers, but the Sherpas have been taking the brunt of the lack of regulation. They are exposed to more dangerous working conditions without an increase of pay.

However, not all the dangers on Everest can be prevented. This study by The Atlantic shows that nearly 50% of hired deaths (meaning Sherpas) were attributed to avalanches.

Back in 2014, there was an avalanche that killed sixteen Sherpas in the Khumbu Icefall, one of the most dangerous areas of the mountain. This was the most deadly incident in the mountain’s history, until almost a year later when 22 people died in the aftermath of the Nepali earthquake. This avalanche inspired the Sherpa community to protest against the Nepali government for better pay and safer working conditions.

In order for their voices to be heard, the Sherpas stated that after the deaths of their colleagues in the avalanche they would not participate in the 2014 Everest climbing season out of respect for the fallen Sherpas. In their absence many climbing companies were forced to return home without attempting Everest, resulting in the loss of thousands of dollars.

In their absence, the Sherpas protested their dangerous working conditions in Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. The Sherpas presented a petition that was signed by only 25 people — many were Sherpas, and the signatories included a few western guides. The petition that was introduced to the Nepal Ministry of Tourism included 13 demands the Sherpas wanted met. Some of the demands included that 30% percent of the $3.5 million of revenue the government collects from the permit fees are used towards rescue operations. For many years Sherpas and climbing companies have been asking for this allocation of funds, but until recently the government ignored this request. According to National Geographic, the Nepali government agreed to use 5% of the permit fees to go to rescue efforts. The Sherpas also demanded that the current $10,000 dollar death benefit be doubled to $20,000. The government later agreed to increase the amount to $15,000. Another change that was made as a result of the 2014 Khumbu Icefall tragedy was that the Nepali authorities announced a new route through the icefall. This route is supposedly a safer way to navigate the treacherous icefall.

Although the Nepali government has made changes to make Everest safer for Sherpas, many argue that this is still not enough. While the cost to climb Everest averages around $50,000 per person, there are still more than 600 attempts each year. The climbing industry in Nepal is worth an annual three and a half million dollars, but very little of that money goes to help the Sherpa community.

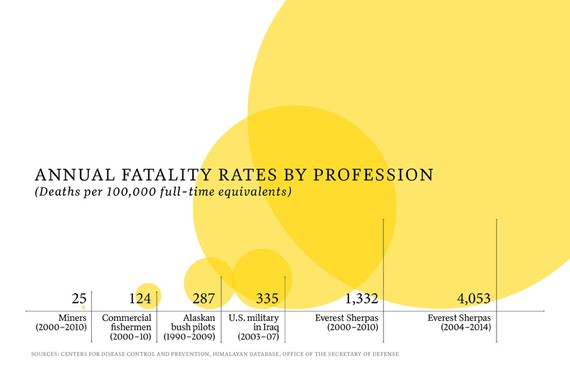

This chart by The Atlantic, shows how being a Sherpa on Everest is the most dangerous job in the world. More dangerous than being an US military service member in Iraq in the early 2000’s. Unfortunately, the job is only becoming more and more dangerous every year. Every climbing season, the Sherpas leave their families knowing the very real possibility that they might never return. With virtually no other options for work, they must do what it takes to provide for their families.

In an interview conducted by HBO, Sherpa Ang Tshering was asked what percent of Sherpas wanted to be porters on Everest. He responded with 80-90 percent of Sherpas “do not want to be there, but every year they always come back”. Tshering continues by saying “it is sad to see, but they are left with no other options to provide for their families”.

Being a porter pays well for an average Nepali lifestyle, but the occupation comes with risks that often outweigh the benefits. The Nepali government has made it clear that it values the foreign cash flow. The Sherpas are risking their lives and their families’ futures for the West’s hobby. The rights of the Sherpas often gets swept under the rug because changes to Everest’s rules and regulations could mean less annual revenue. This situation leaves the mountaineering community with the question- Is climbing Everest ethical?